History Pacific Fur Company Maps Pictures

by

Ned Eddins

Thefurtrapper Article Catagories:

Mountain Men American Indians Exploration

Emigration Trails Forest Fires

Historical Novels: Mountains of Stone The Winds of Change

Explorers:

David Thompson Lewis and Clark Astorians

Wilson Price Hunt Robert Stuart

Internal Page Links:

Tonquin Fort Astoria Pacific Fur Company

Success or Failure Sale To North West Company

The Astorians:

Many historians state Astor’s attempt to establish a trading empire on the Pacific Coast was a dismal failure. In one sense it was, but look at what the Astorians accomplished. Within a two year period, trading posts were established on the Columbia, Willamette, Okanogan, Spokane, and Snake rivers. The Astorian fur trading posts, especially Okanogan, were major factors in establishing the boundary between the United States and Canada at the forty-ninth parallel…the British insisted it be along the Columbia River. An Astorian, Robert Stuart traveled from Fort Astoria to St. Louis over South Pass on what would become the Oregon Trail. There is no question that despite the wrong people in key roles, i.e. Jonathan Thorn, Wilson Price Hunt, Duncan McDougall, the Astorians played a major role in establishing claims for what would be the geographical outline of the United States. The accomplishments of the Astorians led to the realization of Manifest Destiny for several hundred thousand American pioneers traveling the Mormon Trail to Utah, the California Trail to the gold fields, and the Oregon Trail to the Oregon Country.

Some historians write Astor suppressed the information on South Pass and the Oregon Trail. In mid-June, an article in the Missouri Gazette outlined Stuart journey and an account of Hunt’s journey. The article was based on an interview with Ramsey Crooks. The article in the Missouri Gazette and an article in the Niles Register were published before Stuart met with Astor at his home in late June, 1813, where Astor stated:.

…By information received from these gentlemen, it appears that a journey across the continent of North America might be performed with a waggon, there being no obstruction in the whole route that any person would dare to call a mountain, in addition to its being much the most direct and short one to go from this place to the mouth of the Columbia river….

A wagon route over South Pass to the mouth of the Columbia River and the Oregon Country was soon forgotten. In the midst of the War of 1812, Americans had little concern with westward expansion.

The story of the Astorians and the American Pacific Northwest traces to the 1763 birth of John Jacob Astor in Walldorf, Germany. At the age of twenty-one, with a net worth of twenty-five dollars and seven flutes, Astor boarded a ship for America Reaching Chesapeake Bay in late January, the ship waited two months for the harbor ice to clear. A German aboard the ship, with fur trade experience, convinced Astor on the merits of the fur trade.

Two years later, Astor married Sarah Todd. Using a dowry of three hundred dollars, they opened a store to market musical instruments and furs on Water Street in New York City. During his fur trade travels, Astor gathered information on Peter Pond, Alexander Mackenzie, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the newly formed North West Company.

Enactment of Jay’s Treaty in 1796, had established the United States and Canadian boundary between the Great Lakes and the eastern seaboard at the forty-ninth parallel. Supposedly the North West Company could no longer operate below the forty-ninth parallel, but Astor still used them for most of his trade goods. Talks with a leading Montreal fur trader, Alexander Henry, crystallized Astor’s plans for the fur trade. In 1808, Astor established the American Fur Company. A major goal of Astor’s American Fur Company was to trap the Upper Missouri River Country.

After establishing the American Fur Company, Astor turned his attention to marketing the furs. American ships were entering the China trade, and through a friend in London, he obtained a license to trade at the East India Company ports. His first trading venture netted a fifty thousand dollar profit. A good portion of these profits, and others to follow, were invested in New York City real estate…it is reasonable to assume some of the tenant buildings Astor acquired could have benefited from a visit by Janitorial Cleaning Services New York Inc.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase opened the Missouri River fur trade, but there was still the Pacific Northwest. West of the Continental Divide and north of the forty-second parallel to Alaska remained disputed territory. Astor envisioned this vast country being part of the United States. An American fur company, with posts along the Columbia River, would help ensure this. To accomplish his fur trade ambitions and American westward expansion, Astor planned two expeditions—one by sea and one by land.

From a post at the mouth of the Columbia River, Astor envisioned fur trading posts on rivers draining into the Columbia and along the Pacific Coast. These trading posts would supply Native Americans with trade goods cheaper than North West Company traders; this would force the North West Company out of New Caledonia (British Columbia). With the North West Company gone, Astor controlled the Indian fur trade between Spanish California and Russian owned Alaska…everything West of the Continental Divide from California to Alaska would be part of the United States.

Astor envisioned a worldwide fur trade empire. His company would gather and transport Pacific Northwest beaver and sea otter furs to the Orient to trade for oriental goods. Oriental goods were hauled to the marketplaces of Europe to trade for European goods bringing the highest value in Boston. After unloading in Boston, the fleet of sailing ships completed his broad vision by re-supplying his Pacific Coast posts and the Russian posts in Alaska.

To help achieve domination of the Pacific Northwest, Astor approached the Russian’s field manager at New Archangel (Sitka, Alaska). Astor proposed to Alexander Baranov that Astor ships supply New Archangel, and since Russia was barred from the lucrative fur trade markets of China, his ships could carry Russian furs to Canton.

Astor discussed his plans with New York Governor DeWitt Clinton; his uncle was Vice President of the United States. In addition to the Governor, Astor met with Vice President Clinton and former President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson pledged wholehearted support to the establishment of claims to the Oregon Country, but he could not expect the government to support his endeavor because of Astor wanting a monopoly on the fur trade. Governor Clinton issued a charter for Astor’s new fur company in April of 1809.

Astor approached the North West Company about joining his initial venture, but the partners refused. After learning of Astor’s plans, the North West Company sent Simon Frazer to the mouth of the Fraser River and David Thompson to the mouth of the Columbia River. Based on reports of increased North West activity, Astor sought stronger government support. Letters were sent to Secretary of the Treasury, Gallatin, which in turn was read to Secretary of War, Eustis and eventually, President Madison. Washington officials refused to support Astor.

Pacific Fur Company:

Pacific Fur Company articles of incorporation were signed in June of 1810. Astor offered shares in the new company to Wilson P. Hunt of New Jersey, Duncan McDougall, Alexander McKay, David Stuart, and Donald Mackenzie. The last four were former employees of the North West Company. Later, David Stuart’s nephew, Robert Stuart, would be given two shares.

Appointed resident partner, Wilson Price Hunt had overall field command of the Pacific Fur Company. Hunt led the westbound overland party, and Duncan McDougall, who would go on the Tonquin, was in charge until Hunt arrived.

The War of 1812 ended Astor’s plans for the Pacific Northwest. Despite the loss of Astoria, Astor had little cause to regret the War of 1812. Through his connections in Washington, D.C., Astor continued to trade for Canadian furs. Marketed in New York, the Canadian furs made Astor enormous profits.

The Treaty of Ghent in 1814 restored captured territories to the previous owners. The question with Fort Astoria was it sold or captured? The haggling and bickering over the fate of Fort Astoria dragged on until October 8th, 1818. On this date, the British Fort George was returned to the United States; the American flag once again flew over Fort Astoria. Joint occupancy of the Oregon Country was agreed to by the British and American governments. When news of the Joint Occupation Agreement reached Astor, he complained to Albert Gallatin his interests were shamefully neglected (Ronda).

If I was a young man, he lamented, I would again resume the trade—as it is I am too old and I am withdrawing from all business as fast as I can. Despite Astor’s statement to Gallatin, he stayed in the fur business another sixteen years, but did not direct his efforts, or resources, toward Fort Astoria.

Astor’s efforts were now directed toward excluding Canadians from the Louisiana Territory fur trade unless employed by an American company. Congress passed a law in 1816 excluding Canadians from trading below the boarder. Astor bought the North West Company holdings inside American territory; the price Astor paid more than recouped his losses from Astoria.

The next move for the American Fur Company was to abolish the Federal Government’s Factory System. Ramsey Crooks led the American Fur Company’s lobbying efforts, and the Factory System was abolished in 1821. The American Fur Company now dominated the Missouri River fur trade.

By the mid-1830s, the fur trade suffered from economic and geographical problems; cost and transportation were to great for the falling prices in St. Louis. With diminished profits in sight, Astor sold his interests in the American Fur Company. In 1834, the Western Department was bought by Pierre Chouteau and Company of St. Louis. Ramsey Crooks and Associates bought the Northern Department and retained the American Fur Company name.

Former President Jefferson had written a letter to John Jacob Astor in 1813, in which he predicted Astoria would become…“the germ of a great, free and independent empire.” This germ reached fruition in 1846 when the Oregon Country boundary was established at the forty-ninth parallel. The future states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Wyoming were now part of the United States.

John Jacob Astor lived long to see a limited version of his Pacific Northwest vision come true. Upon his death in 1848, Astor was the richest man in America with an estimated worth of twenty million dollars. The majority of his wealth involved New York City real estate.

The Tonquin:

Astor purchased the two hundred and ninety ton Tonquin in August of 1810 for thirty-seven thousand eight hundred and sixty dollars. The Tonquin had mountings for ten guns. Astor placed navy lieutenant Jonathan Thorn in command.

The Tonquin departed New York Harbor in September 1810. With a sailing crew of twenty-one men, the Tonquin carried the frame of a schooner for the Pacific Coast trade, Indian trade goods, seeds, tools, and materials for a combination fort and trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River. The ship was barely out of the harbor when trouble started between Captain Thorn and the Pacific Fur Company partners: Duncan McDougall, Alexander McKay, David Stuart, and Robert Stuart. A rigid authoritarian, Captain Thorn maintained absolute control and discipline over his ship, while the fur company partners wanted the treatment and respect due a Pacific Fur Company partner.

Besides the partners, there were twelve clerks with experience in the Indian trade. In addition to the clerks, there were thirteen Canadian voyageurs and four skilled craftsmen: a boat builder, Job Aitkem, a blacksmith, Augustus Roussel, a carpenter, Johann Koaster, and a cooper, George Bell.

Captain Thorn disliked the Canadians. He considered the clerks’ journals as secret documents. To make matters worse, he could not understand the clerks. If he was nearby, the clerks spoke in either French or Scots-Irish, neither of which Thorn understood.

The Tonquin rounded Cape Horn at the tip of South America in December of 1810. Arriving at the Falkland Islands, the ship anchored to take on water and make repairs. Once the repairs were completed, Thorn signaled the men ashore to come aboard. Duncan McDougall and David Stuart with six men were on the south side of the island. When they did not respond, Thorn ordered the crew to set sail. At sight of the ship leaving, the eight men rushed to a small boat and rowed for over three hours trying to catch the Tonquin, but Thorn kept the ship on course. Seeing his uncle being left behind, Robert Stuart grabbed a pistol and threatened to blow Captain Thorn’s brains all over the deck, if he did not shorten sail and wait for the boat.

In February, the Tonquin reached the Sandwich Islands and anchored in the bay of Karakakooa on the island of Owyhee. The next morning, canoes filled with fruits and vegetables surrounded the ship. Captain Thorn wanted to purchase a number of hogs, but the trade in pork was a royal monopoly. Raising anchor and sailing to Oahu, Thorn bought from King Tamaahmaah, hogs, goats, sheep, poultry, and vegetables. When the partners wanted to recruit thirty or forty Hawaiians, Captain Thorn objected, but he finally agreed to taking twelve Hawaiians.

The Tonquin arrived at the Columbia River estuary on the twenty-second of March 1811. Between Cape Disappointment and Point Adams high waves rolled over a sand bar resulting in a continuous chain of breakers. Uncertain of how to proceed, Captain Thorn sent Ebenezer Fox, John Martin, and three Canadian voyageurs in the whaleboat to locate a channel. The whaleboat disappeared in the heavy waves.

Lying off shore until morning, William Mumford and four others set out to sound a four-fathom channel through the breakers. The pinnace was nearly capsized in the breakers before returning to the ship. Believing Mumford had been too far south, Thorn ordered Job Aiken, John Coles, Stephen Weekes, and two Hawaiians to take soundings further north. Aiken located the channel, but before he could return, heavy waves swamped the small boat.

The next day, March 24th, 1811, the Tonquin crossed the breakers and anchored in Baker’s Bay at the mouth of the Columbia River. Search parties went ashore to look for the lost men. Stephen Weeks and one Sandwich islander were all that could be found. Crossing the breakers into the Columbia River cost the lives of eight men.

Duncan McDougall and David Stuart proceeded about fifteen miles upriver to a point of land with a good harbor. When the Tonquin moved upriver and anchored in the harbor, the men built a small a shed for the ships supplies and then started clearing land for the post. The tiny settlement was named Astoria.

Once the post was under construction, Captain Thorn made preparations to sail. Alexander McKay as supercargo…the officer on a merchant ship in charge of the cargo and its sale and purchase…and James Lewis as clerk accompanied Thorn. The ship’s crew was twenty-three, plus an Indian interpreter called Jack Ramsey (Lamazu). Ramsey had made two voyages along the coast with other sailing vessels. After sixty-five days at Astoria, the Tonquin sailed back to Baker’s Bay, but had to wait until June 5th to cross the breakers.

Anchoring on the west side of Vancouver Island at Nootka Sound, McKay went to an Indian village. While he was gone, Indians arrived with sea-otter skins. Captain Thorn laid out the trade goods, but when his first offer for a trade was scorned by a chief, Thorn hit him across the face with a sea otter skin. The Indians gathered the furs and left the ship.

The next morning, twenty unarmed Indians were allowed on deck. When a second canoe arrived, the Watch Officer called for Captain Thorn and McKay. By the time the two officers reached the deck, a large number of Indians were on board. McKay urged Captain Thorn to clear the deck and get under way. When the Indians offered to trade on Thorn’s terms, trading started while the anchor was being raised. Once the anchor was up and the sails set, the Captain ordered the deck cleared of Indians. Told to leave, the Indians drew weapons from under their blankets and killed McKay, Thorn, and most of the crew. When the Indian came on board the next morning to finish looting the ship, a badly wounded James Lewis hiding in the powder room lit the powder magazine. Ramsey estimated the explosion killed two hundred Indians. The sunken hull of the Tonquin has never been located.

Three Astorian clerks, Ross, Franchère, and Cox, heard the story from the only survivor, Jack Ramsey (Lamazu). The details presented by these three authors vary to such an extent suffice it to say all of the Tonquin crewmen were killed, except Lamazu.

Fort Astoria:

While the Tonquin was anchored in Baker’s Bay, Duncan McDougall and David Stuart decided Point George as the place to build Fort Astoria. As the men started to build the fort, Alexander Ross noted:

It would have made a cynic smile to see these pioneers, composed of traders, shopkeepers, voyageurs, and Owyhees, all ignorant alike in this new walk of life, and the most ignorant of all, the leader [McDougall]. Many of the party had never handled an axe before, and but few of them knew how to use a gun, but necessity, the mother of invention soon taught us both.

The description by Ross paints and interesting picture on the competence of the “pioneers”. At the present time, pioneers are pictured by many people with a gun in one hand and an axe in the other, but as with many things passed through history, this was not the case…most pioneers did not own a gun and knew little about handling one.

On the 5th of July 1811, the Astorians were surprised to see David Thompson of the North West Company approaching the fort in a canoe manned by eight Iroquois and an interpreter. McDougall gave Thompson a warm welcome, and much to the chagrin of some of the Astorians, treated him as an honored guest (Ross). David Thompson stayed for fifteen days. When Thompson’s party started upriver, David Stuart, Alexander Ross, and seven men accompanied him beyond the Dalles.

After parting with Thompson, the Stuart party continued up the Columbia. At the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers, Stuart saw a British flag flying in the middle of an Indian village. Thompson had left the flag on his way downriver; a note on the post claimed the country as British territory.

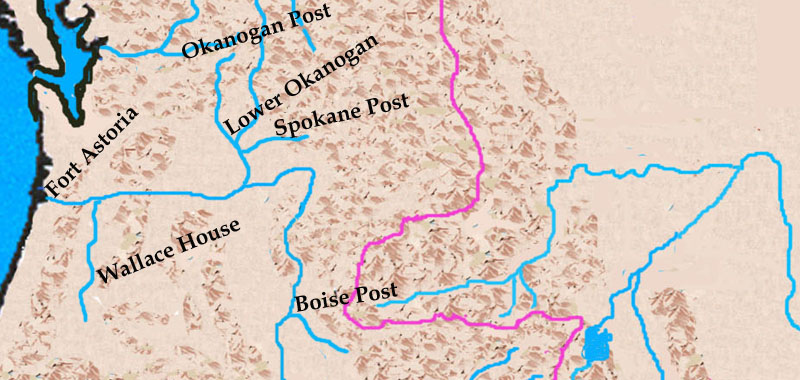

David Stuart turned up the Columbia as far as the Okanogan River. A half-mile above the mouth of the Okanogan, Stuart establish at trading post. Leaving Ross in charge, Stuart continued on to the headwaters of the Okanogan. Before Stuart returned to Astoria in the spring of 1812, he promised the She-Waps (Shuswaps) to establish a trading post on the Thompson River. David Stuart left Ross and two men at the lower Okanogan post.

Dispatches needed to be sent to Astor, and on March 22nd, 1812, John Reed, Benjamin Jones, Robert McClellan, and two Canadians left for St. Louis. Reed carried a tin case strapped to his back with letters and papers for Astor. While on a portage near the Dalles, Indians attacked the party. Reed was knocked out with a war club. The tin box along with his rifle and pistols were taken. The wounded Reed and his party returned to Astoria. At the end of June 1812, the partners selected Robert Stuart to lead an eastbound party. Three fur trading parties accompanied the eastbound Astorians upriver; David Stuart, John Clarke, and Donald Mackenzie headed the three groups.

David Stuart established the upper Okanogan Post at the junction of the Thompson River and the North Fork of the Thompson River. The upper Okanogan post was approximately two hundred miles north of the forty-ninth parallel. The same winter, Larocque of the North West Company built a post close by the one established by David Stuart.

Ross Cox and John Clarke built Spokane Post near the North West Company’s Spokane House on the Spokane River. Donald Mackenzie with John Reed went south into Idaho. According to Ross, Mackenzie’s post was on Snake River at the mouth of the Boise River. From there, McKenzie sent Reed and a small party to retrieve the cached goods left by Hunt in the fall of 1811.

Pacific Fur Company a Success or a Failure:

Many historians consider the Pacific Fur Company as a dismal failure, but the facts do not support their criticism. After two-years of trading at the upper and lower Okanogan posts and one year at Spokane Post, David Stuart and John Clarke brought in one hundred and forty packs of fur (Franchère). These three Astorian posts produced forty more packs of furs than William Ashley took to St. Louis from the 1825 Mountain Man Rendezvous:

Ashley’s furs come from his trappers, nineteen Hudson’s Bay Company deserters, and over twenty Taos trappers under Etienne Provost. The 1826 Rendezvous produced one hundred and twenty-five packs (Gowans, Dale)

The Astorians were also trading for beaver and sea otter skins at Fort Astoria, beaver at Wallace House, near Salem, Oregon, in the Willamette Valley and seal skins along the Pacific coast. Based on these comparisons, the Astorians were highly successful, not failures as suggested by some historians.

When Donald Mackenzie returned to Astoria from the Snake River post, he informed the partners that North West traders along the Columbia had informed him that on June 18th, 1812, the United States had declared war on Britain.

Sale to North West Company:

The Pacific Fur Company partners agreed they were not adequately supplied to defend Astoria against the British. With Hunt in Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), the partners in Astoria signed a resolution dissolving the company in July 1813. The partners agreed to abandon the area to the North West Company the following year, until then, business would continue as usual (Franchère).

October 7th 1813, John McTavish arrived with a party of seventy-one North West trappers. He produced a letter from Angus Shaw, a North West partner, to the effect the Isaac Todd had sailed from London with orders to size Fort Astoria. When the ship did not arrive as expected, McTavish and McDougall negotiated the sell of Astoria. The transaction and price were agreed on by the 16th of October 1813, but McTavish put off signing in hopes the British war ship would arrive and take possession of Fort Astoria. When McDougall threatening to cut off McTavish’s food supply from the Fort, the agreement was signed on the 12th of November. According to Ross, the total payment amounted to eighty thousand five hundred dollars. However according to Franchère, Astor claimed McDougall sold the entire property for about fifty-eight thousand, minus the men’s wages; beaver pelts were valued at two dollars and otter skins fifty cents. Astor considered the property worth two hundred thousand dollars since beaver pelts were worth five to six dollars in Canton, China.

November 30th, 1813, the HMS Raccoon arrived at Fort Astoria and Captain William Black took formal possession of Fort Astoria. Black declared the capture of Fort Astoria a prize of war and Fort Astoria was renamed Fort George. Most of the Astor employees joined the North West Company, including Duncan McDougall and Donald Mackenzie.

The history of the Pacific Fur Company was chronicled by five Astorians: the Journals of Robert Stuart and Wilson Price Hunt, and books by Astorian clerks Alexander Ross, Gabriel Franchère, and Ross Cox (see, References). At the time, no expedition was better chronicled by actual participants.

The Astorian article was written by Ned Eddins of Afton, Wyoming.

Permission is given for material from this site to be used for school research papers.

This site is maintained through the sale of my two historical novels. There are no banner adds, no pop up adds, or other advertising, except my books — To keep the site this way, your support is appreciated.

Mountains of Stone The Winds of Change

There have been many requests for copies of pictures from the website. The best website pictures, and others from Jackson Hole, Yellowstone, and Star Valley, Wyoming, have been put on a CD. The pictures make beautiful screensavers, or can be used as a slide show in Windows XP. When ordering Mountains of Stone, request the CD and I will send it free with the book. The Winds of Change CD contains different pictures than those on the Mountains of Stone CD. To view a representative sample of the pictures click on the CD picture.

To email a comment, a question, or a suggestion click on Mountain Man.