The Oregon Trail History and Trail Sites

by

Ned Eddins

Thefurtrapper Article Catagories:

Mountain Men American Indians Exploration

Emigration Trails Forest Fires

Historical Novels: Mountains of Stone The Winds of Change

Western Expansion:

Oregon-California Trail Oregon Country Mormon Trail

Lander Cutoff Handcart Companies South Pass

Hole-in-the-Rock Trail Sarah Crossley Sessions

Page Links:

America’s Western Expansion Mormon-Oregon-California Trail

The Oregon Trail article is not a day by day account of travel, but a series of factual historical trivia related to the Oregon Country, Western Expansion, and the Oregon Trail.

The Oregon Trail pioneered by the Astorians in 1812 eventually opened up a new way of life for a great many Americans. The first non-missionary family to farm in Oregon Country traveled the Oregon Trail in 1840. This was the family of Joel Walker, the brother of mountain man Joseph Walker. By the same token, the Oregon Trail sounded the death knell for a great many American Indians. The first settlers over South Pass on the Oregon Trail signaled the end for millions of buffalo and the Plains Indians.

Forty-six years after the first pioneers traveled the Oregon Trail…the last buffalo hunt was held in the Judith Valley, and the vast majority of Plains Indians were on reservations.

As this country expanded and defined itself, there is no doubt tragedies occurred, i. e. Trail of Tears, Moravian Massacre. Similar wrongs have happened throughout world history, and are still happening today in Russia, many third world countries, and Muslim countries. Despite what we may want to believe, this has been the pattern for all developing countries, and it was going on long before there was an America. From a biblical sense, it started with Cain and Abel.

The history of the Oregon, Mormon, and California trails cannot be separated from the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade. Mountain men not only trapped and explored the way West, with the exception of the Mormon Trail, mountain men led the first wagon trains over the trails.

A great many people paid a huge price to live, or even survive, in the West. Oregon Trail pioneers struggled West for free land and a better life; Mormon emigrants went West to escape religious persecution. White Americans took the land from Native Americans that had taken the land from other Native Americans. Striving for a better life, religious persecution, and one people taken another peoples land are cornerstones of World History.

Prior to 1846, the Oregon Country was the territory west of the Continental Divide from northern California to the southern border of Alaska. The settlement of the Oregon Country boundary at the forty-ninth parallel in 1846, and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848 brought the future western states of Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Idaho, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, New Mexico, and Arizona under the American flag.

America’s Western Expansion:

For the Mexican government to give up almost half of Mexico, the American government paid Mexico fifteen million dollars and assumed debts of three million two hundred and fifty thousand dollars for a total of eighteen million two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Part of this settlement was the Mexican Government relinquishing any claims over the annexing of Texas into the Union.

For the Mexican government to give up almost half of Mexico, the American government paid Mexico fifteen million dollars and assumed debts of three million two hundred and fifty thousand dollars for a total of eighteen million two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Part of this settlement was the Mexican Government relinquishing any claims over the annexing of Texas into the Union.

The Guadalupe Hidalgo treaty increased the size of the United States by about one-third (this includes Texas)–an addition greater than the Louisiana Purchase.

The Guadalupe Hidalgo treaty increased the size of the United States by about one-third (this includes Texas)–an addition greater than the Louisiana Purchase.

At various times, Spain, Russia, England, and the United States claimed the Oregon Country. The only people with a real claim on the land were the American Indians.

At various times, Spain, Russia, England, and the United States claimed the Oregon Country. The only people with a real claim on the land were the American Indians.

Why didn’t the American Indians have any say in the Oregon Country settlement? The reason is:In 1452, the Catholic Pope Nicholas V issued to King Alfonso V of Portugal a proclamation declaring war against all non-Christians throughout the world, and specifically sanctioning and promoting the conquest, colonization, and exploitation of non-Christian nations and their territories. This “Doctrine of Discovery” gave Christian countries the rights to the lands of non-Christians.

Why didn’t the American Indians have any say in the Oregon Country settlement? The reason is:In 1452, the Catholic Pope Nicholas V issued to King Alfonso V of Portugal a proclamation declaring war against all non-Christians throughout the world, and specifically sanctioning and promoting the conquest, colonization, and exploitation of non-Christian nations and their territories. This “Doctrine of Discovery” gave Christian countries the rights to the lands of non-Christians.

In 1823, the United States Supreme Court decided in the Johnson v. McIntosh decision that, “as a result of European discovery, the Native Americans had a right to occupancy and possession.” But “tribal rights to complete sovereignty were necessarily diminished by the principle discovery gave exclusive title to those who made it.” Chief Justice John Marshall observed that European nations had assumed “ultimate dominion” over the lands of America during the Age of Discovery, and that upon “discovery” the Indians lost “their rights to complete sovereignty, as independent nations,” and retained only a right of “occupancy” in their lands”

In 1823, the United States Supreme Court decided in the Johnson v. McIntosh decision that, “as a result of European discovery, the Native Americans had a right to occupancy and possession.” But “tribal rights to complete sovereignty were necessarily diminished by the principle discovery gave exclusive title to those who made it.” Chief Justice John Marshall observed that European nations had assumed “ultimate dominion” over the lands of America during the Age of Discovery, and that upon “discovery” the Indians lost “their rights to complete sovereignty, as independent nations,” and retained only a right of “occupancy” in their lands”

It was the Doctrine of Discovery that gave Rene-Robert La Salle the right to stand at the mouth of the Mississippi River and declare all the drainage of the Mississippi River belonged to the King of France.

It was the Doctrine of Discovery that gave Rene-Robert La Salle the right to stand at the mouth of the Mississippi River and declare all the drainage of the Mississippi River belonged to the King of France.

The 1823 opinion on the Doctrine of Discovery by Chief Justice John Marshal is still upheld by the United States Legal system.

The 1823 opinion on the Doctrine of Discovery by Chief Justice John Marshal is still upheld by the United States Legal system.

In 1806, Lt. Zebulon Pike explored the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountains. Lt. Pike referred to the plains as “the Great American Desert”. Pike’s opinion was confirmed by Major Steven Long, who led an expedition West in 1819. Major Long concluded the entire region was unfit for human habitation.

In 1806, Lt. Zebulon Pike explored the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountains. Lt. Pike referred to the plains as “the Great American Desert”. Pike’s opinion was confirmed by Major Steven Long, who led an expedition West in 1819. Major Long concluded the entire region was unfit for human habitation.

William Ashley expressed similar view as Lt. Pike in a letter to Fort Atkinson. And so, any route to the Oregon Country was of little interest to most people until 1840 when the first homesteader traveled over what would be the Oregon Trail.

William Ashley expressed similar view as Lt. Pike in a letter to Fort Atkinson. And so, any route to the Oregon Country was of little interest to most people until 1840 when the first homesteader traveled over what would be the Oregon Trail.

The Astorian Robert Stuart and six men were the first non-Indians to travel over what would become the Oregon Trail in 1812.

The Astorian Robert Stuart and six men were the first non-Indians to travel over what would become the Oregon Trail in 1812.

The depression following the War of 1812 left little interest in western expansion despite a Missouri Gazette editorial on Stuart’s path being an easy wagon route to the Oregon Country.

The depression following the War of 1812 left little interest in western expansion despite a Missouri Gazette editorial on Stuart’s path being an easy wagon route to the Oregon Country.

The Oregon Trail is is the only major trail in the United States that was first traveled in a west to east direction.

The Oregon Trail is is the only major trail in the United States that was first traveled in a west to east direction.

Mormon – Oregon – California Trail:

There was little national interest in a trail to the West until Jedediah Smith crossed South Pass in 1824. Smith is given credit for the effective discovery of South Pass.

There was little national interest in a trail to the West until Jedediah Smith crossed South Pass in 1824. Smith is given credit for the effective discovery of South Pass.

T he number one traveler of the Oregon trail was Ezra Meeker. Meeker went over the Oregon Trail in 1852. At the age of 76, Meeker, accompanied by two oxen, a driver and a dog, went from Puyallup, Washington to Washington, D.C.. Meeker wanted to bring the Nation’s attention to the Oregon Trail, which was being plowed under by civilization.

he number one traveler of the Oregon trail was Ezra Meeker. Meeker went over the Oregon Trail in 1852. At the age of 76, Meeker, accompanied by two oxen, a driver and a dog, went from Puyallup, Washington to Washington, D.C.. Meeker wanted to bring the Nation’s attention to the Oregon Trail, which was being plowed under by civilization.

Ezra Meeker made three more journeys to the East: another with an ox team, by an automobile in 1915, and by an airplane in 1924. The “Champion” of the Oregon Trail died at the age of ninety-eight.

Ezra Meeker made three more journeys to the East: another with an ox team, by an automobile in 1915, and by an airplane in 1924. The “Champion” of the Oregon Trail died at the age of ninety-eight.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and Henry and Elisa Spaulding traveled to the 1836 Horse Creek Rendezvous with two wagons. On the advise of several mountain men, the heaviest wagon was left at the Horse Creek Rendezvous, but Dr. Whitman refused to leave the light wagon. At Fort Hall, Doctor Whitman’s driver deserted, and the wagon was made into a two-wheeled cart.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and Henry and Elisa Spaulding traveled to the 1836 Horse Creek Rendezvous with two wagons. On the advise of several mountain men, the heaviest wagon was left at the Horse Creek Rendezvous, but Dr. Whitman refused to leave the light wagon. At Fort Hall, Doctor Whitman’s driver deserted, and the wagon was made into a two-wheeled cart.

At Fort Boise, Dr. Spaulding relinquished the idea of taking the cart over the Blue Mountains. The two-wheeled cart was abandoned at Fort Boise…many internet sites claim the Whitmans traveled all the way to Washington in a covered wagon.

At Fort Boise, Dr. Spaulding relinquished the idea of taking the cart over the Blue Mountains. The two-wheeled cart was abandoned at Fort Boise…many internet sites claim the Whitmans traveled all the way to Washington in a covered wagon.

Oregon Trail pioneers were mostly middle class, successful people. Eight hundred to a thousand dollars were required for a wagon, oxen, and enough supplies to live a year.

Oregon Trail pioneers were mostly middle class, successful people. Eight hundred to a thousand dollars were required for a wagon, oxen, and enough supplies to live a year.

Of the men on the Oregon Trail, sixty percent of the family men were farmers. Around twenty percent of the men were craftsmen and merchants, while physicians, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals made up about twelve percent.

Of the men on the Oregon Trail, sixty percent of the family men were farmers. Around twenty percent of the men were craftsmen and merchants, while physicians, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals made up about twelve percent.

On the Oregon Trail, one in every five women were in some stage of pregnancy. Nearly all married woman traveled with small children.Many pioneer families had a milk cow tied to the tailgate of the wagon.

On the Oregon Trail, one in every five women were in some stage of pregnancy. Nearly all married woman traveled with small children.Many pioneer families had a milk cow tied to the tailgate of the wagon.

After milking the cow, the milk sat until the cream raised to the top. Each morning, the cream was poured into a churn carried in or on the side of the wagon. As the churn bounced along over the rough trail, the cream turned to butter.

After milking the cow, the milk sat until the cream raised to the top. Each morning, the cream was poured into a churn carried in or on the side of the wagon. As the churn bounced along over the rough trail, the cream turned to butter.

One estimate has one of every seventeen travelers (men, women, children) dying in route to the Oregon Country (Bailey).

One estimate has one of every seventeen travelers (men, women, children) dying in route to the Oregon Country (Bailey).

A noted historian, Merrill Mattes used a conservative figure of twenty thousand deaths over a twenty year period for the entire two thousand miles of the Oregon Trail.

A noted historian, Merrill Mattes used a conservative figure of twenty thousand deaths over a twenty year period for the entire two thousand miles of the Oregon Trail.

The number of deaths on the Oregon Trail (1843-1863) used by Mattes corresponds to a grave every one hundred and sixty-seven yards, or ten graves per mile.

The number of deaths on the Oregon Trail (1843-1863) used by Mattes corresponds to a grave every one hundred and sixty-seven yards, or ten graves per mile.

Between 1849 and 1853, the greatest killer on the trail was a bacterial infection causing a watery diarrhea…Cholera. The major source of the bacteria was from the stagnant water along the trail.

Between 1849 and 1853, the greatest killer on the trail was a bacterial infection causing a watery diarrhea…Cholera. The major source of the bacteria was from the stagnant water along the trail.

Across Nebraska was the deadliest area for cholera. Ninety-six percent of all cholera deaths occurred prior to reaching South Pass. Cholera was first reported in the United States between 1832-1834. In the early 1850s, St. Louis lost a tenth of its population to this disease, including my great-great grandfather Mathew Gilby and five of his six children.

Across Nebraska was the deadliest area for cholera. Ninety-six percent of all cholera deaths occurred prior to reaching South Pass. Cholera was first reported in the United States between 1832-1834. In the early 1850s, St. Louis lost a tenth of its population to this disease, including my great-great grandfather Mathew Gilby and five of his six children.

Cholera continued to appear during the 1850’s, but its appearance diminished after 1853.

Cholera continued to appear during the 1850’s, but its appearance diminished after 1853.

After cholera, wagon accidents, crossing rivers, and accidental gun shot wounds accounted for most of the Oregon Trail deaths.

After cholera, wagon accidents, crossing rivers, and accidental gun shot wounds accounted for most of the Oregon Trail deaths.

Hundreds of children and adults drowned trying to cross the Kansas, Platte, North Platte, Green, Snake, and Columbia rivers. Small creeks accounted for many deaths as well.

Hundreds of children and adults drowned trying to cross the Kansas, Platte, North Platte, Green, Snake, and Columbia rivers. Small creeks accounted for many deaths as well.

Despite Hollywood’s “Indians circling the wagons”, it is estimated three hundred and fifty to four hundred emigrants were killed between 1840 and 1860 by Native Americans. The number of people killed by Indians is close to the number of pioneers dying from drowning and accidental gun shot wounds.

Despite Hollywood’s “Indians circling the wagons”, it is estimated three hundred and fifty to four hundred emigrants were killed between 1840 and 1860 by Native Americans. The number of people killed by Indians is close to the number of pioneers dying from drowning and accidental gun shot wounds.

Pioneers frequently used a “Roadside Telegraph.” Messages, on scraps of cloth, animal skulls, rocks, bark, leaves, etc., were left beside the trail for other wagon trains, or hopefully, someone would carry a message back East.

Pioneers frequently used a “Roadside Telegraph.” Messages, on scraps of cloth, animal skulls, rocks, bark, leaves, etc., were left beside the trail for other wagon trains, or hopefully, someone would carry a message back East.

From 1841 to 1848, wagons on the 2,000 mile Oregon Trail averaged about eighty-five miles a week. With one day a week for repairs and rest, this averaged about fourteen miles per day. John Unruh, Jr. estimated the average number of days to reach California or Oregon:

From 1841 to 1848, wagons on the 2,000 mile Oregon Trail averaged about eighty-five miles a week. With one day a week for repairs and rest, this averaged about fourteen miles per day. John Unruh, Jr. estimated the average number of days to reach California or Oregon:

1841-1848: California: 157.7 Oregon: 169.1

1849: California: 131.6 Oregon: 129.0

1850: California: 107.9 Oregon: 125.0

1850-60: California: 112.7 Oregon: 128.5

1841-1860: California: 121.0 Oregon: 139.6

From 1840 to 1860, the total number of people traveling the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails is estimated at 320,000. If the time frame is expanded to a twenty-nine year period, it is estimated over 500,000 Oregon and Mormon pioneers and California gold seekers traveled the trails.

From 1840 to 1860, the total number of people traveling the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails is estimated at 320,000. If the time frame is expanded to a twenty-nine year period, it is estimated over 500,000 Oregon and Mormon pioneers and California gold seekers traveled the trails.

The glory years of the Oregon Trail and Mormon Trail ended with the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point, Utah in 1869. The Oregon Trail travel was greatly diminished after 1869, but it was still occasionally used during the Civil War and as late as 1880.

The glory years of the Oregon Trail and Mormon Trail ended with the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point, Utah in 1869. The Oregon Trail travel was greatly diminished after 1869, but it was still occasionally used during the Civil War and as late as 1880.

Mountain men who had explored the country in search of beaver often led the wagon trains over the Oregon Trail. Two of the most famous guides were Thomas Fitzpatrick and Moses “Black” Harris.

Mountain men who had explored the country in search of beaver often led the wagon trains over the Oregon Trail. Two of the most famous guides were Thomas Fitzpatrick and Moses “Black” Harris.

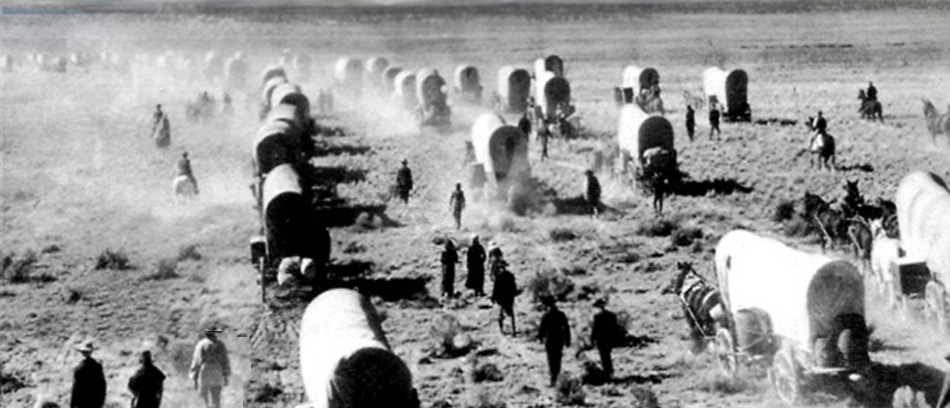

Conestoga wagons were too big for the Oregon Trail. Converted farm wagons, called Prairie Schooners were used with primarily oxen pulling them. The oxen were driven by a man or woman walking along side.

Conestoga wagons were too big for the Oregon Trail. Converted farm wagons, called Prairie Schooners were used with primarily oxen pulling them. The oxen were driven by a man or woman walking along side.

Some Indians called the Prairie Schooners, “horsecanoes” or “winged canoes”, and the Oregon Trail as “the Great Medicine Road.”

Some Indians called the Prairie Schooners, “horsecanoes” or “winged canoes”, and the Oregon Trail as “the Great Medicine Road.”

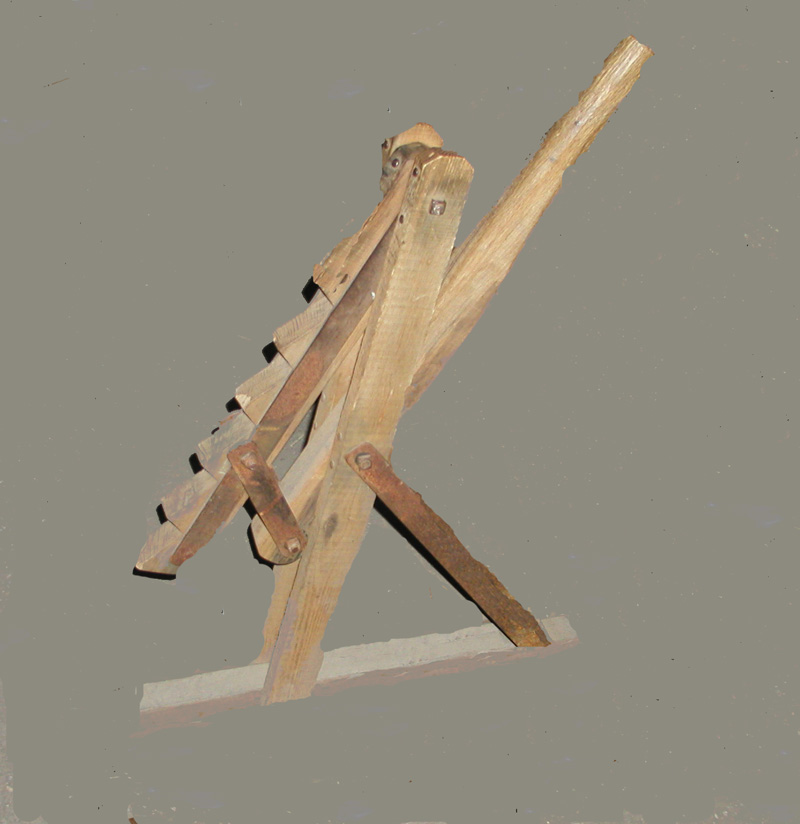

A wagon jack was often carried in a wagon train. The above wagon jack is courtesy of the Oregon California Trail Center in Montpelier, Idaho. The Oregon Trail Interruptive Center is actually located on the Oregon Trail.

A wagon jack was often carried in a wagon train. The above wagon jack is courtesy of the Oregon California Trail Center in Montpelier, Idaho. The Oregon Trail Interruptive Center is actually located on the Oregon Trail.

The Oregon Trail Center has an excellent hands-on interruptive program along with a pioneer and railroad museum.

The Oregon Trail Center has an excellent hands-on interruptive program along with a pioneer and railroad museum.

After a few days on the trail, the travelers settled into a well-defined daily routine. Wake before sunup, catch and yoke the oxen, cook breakfast (usually warm johnnycakes and bacon) and hit the trail. There was an hour break for lunch, and at about 6 p.m., the wagon trains stopped for the night.

After a few days on the trail, the travelers settled into a well-defined daily routine. Wake before sunup, catch and yoke the oxen, cook breakfast (usually warm johnnycakes and bacon) and hit the trail. There was an hour break for lunch, and at about 6 p.m., the wagon trains stopped for the night.

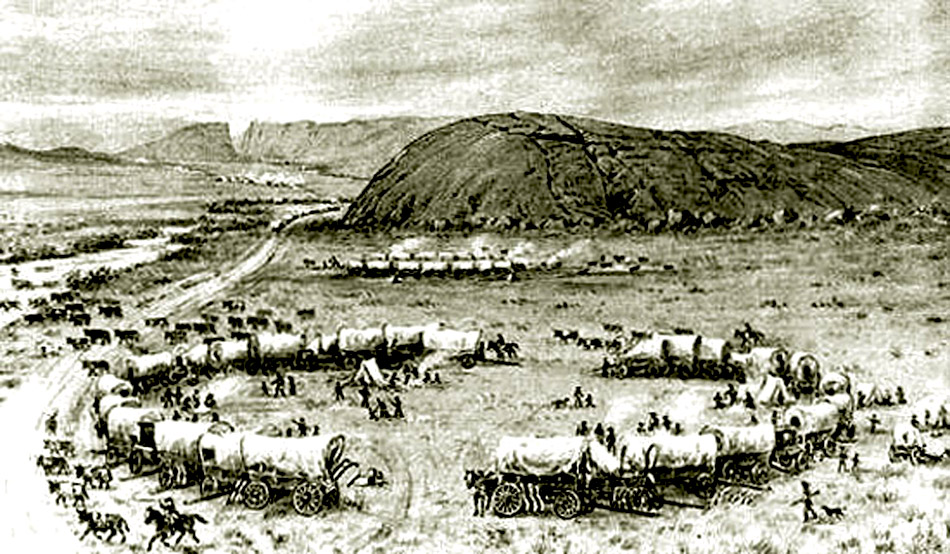

It is often stated in pioneer journals the wagons were circled at night to provided a corral for the livestock.

It is often stated in pioneer journals the wagons were circled at night to provided a corral for the livestock.

This I doubt, and have been criticized for writing it. A wagon train of say one hundred wagons would have at least four-to-six hundred oxen or more, milk cows, draft horses, and saddle horses. A hundred wagons could not make a circle big enough to hold this many animals. Another question is what did the animals eat? The grass inside any circle would be tramped down and covered with several inches of manure in a matter of hours.

This I doubt, and have been criticized for writing it. A wagon train of say one hundred wagons would have at least four-to-six hundred oxen or more, milk cows, draft horses, and saddle horses. A hundred wagons could not make a circle big enough to hold this many animals. Another question is what did the animals eat? The grass inside any circle would be tramped down and covered with several inches of manure in a matter of hours.

In the vast semi-arid areas of the Oregon Trail, animals had to eat at least ten-to-twelve hours at night for enough strength to pull the wagons and produce milk.

In the vast semi-arid areas of the Oregon Trail, animals had to eat at least ten-to-twelve hours at night for enough strength to pull the wagons and produce milk.

Quality of the grasses was the main reason oxen were used instead of horses. Oxen can work on a poorer nutritional diet than horses. There are many journal accounts of a late start in the morning because the belled oxen could not be found.

Quality of the grasses was the main reason oxen were used instead of horses. Oxen can work on a poorer nutritional diet than horses. There are many journal accounts of a late start in the morning because the belled oxen could not be found.

Made in France, this bell is twelve by six inches. Copied by Mormon blacksmiths, these bells were often called the Nauvoo bells by Mormon pioneers. Strapped around the neck of oxen, the clanking bell made it easier to find the oxen when turned loose to feed.

Made in France, this bell is twelve by six inches. Copied by Mormon blacksmiths, these bells were often called the Nauvoo bells by Mormon pioneers. Strapped around the neck of oxen, the clanking bell made it easier to find the oxen when turned loose to feed.

Oxen are called steers up to three years old, after that the steer was called an ox. A pair of oxen weighed up to three thousand pounds.

Oxen are called steers up to three years old, after that the steer was called an ox. A pair of oxen weighed up to three thousand pounds.

Journals kept by mountain men, pioneers, and emigrants are often the only primary source of information, but they are not necessarily factual. Seldom do writers see the same event in the same way; two examples are the Battle of Pierre’s Hole and the Tonquin disaster. Just as many writers (and newsmen) of today, the early writers tended to over emphasize the bad and exciting parts and leave out the endless days of boredom. This tends to give the reader, as well as history, a distorted view of the actual happenings.

Journals kept by mountain men, pioneers, and emigrants are often the only primary source of information, but they are not necessarily factual. Seldom do writers see the same event in the same way; two examples are the Battle of Pierre’s Hole and the Tonquin disaster. Just as many writers (and newsmen) of today, the early writers tended to over emphasize the bad and exciting parts and leave out the endless days of boredom. This tends to give the reader, as well as history, a distorted view of the actual happenings.

Many journals were not kept on a day to day basis, especially mountain man journals. Pioneer journals that were “added to or brought up to date” are influenced by other pioneers comments and writings.

Many journals were not kept on a day to day basis, especially mountain man journals. Pioneer journals that were “added to or brought up to date” are influenced by other pioneers comments and writings.

Distorted views are also obtained from oral histories or traditions. Oral histories are stories handed down from one generation to the next…they are stories not fact.

Distorted views are also obtained from oral histories or traditions. Oral histories are stories handed down from one generation to the next…they are stories not fact.

An ethnologist, Dr. George Grinnell lived with the Cheyenne Indians for several different years. Dr. Grinnell findings showed oral histories were relative accurate for three generations…after that oral histories were stories; the same is undoubtedly true of handed-down white oral histories.

An ethnologist, Dr. George Grinnell lived with the Cheyenne Indians for several different years. Dr. Grinnell findings showed oral histories were relative accurate for three generations…after that oral histories were stories; the same is undoubtedly true of handed-down white oral histories.

Independence, Missouri was the major departure point in the early years of the Oregon Trail. A former slave Hiram Young owned the largest business in Independence: he made wagons and ox yokes.

Independence, Missouri was the major departure point in the early years of the Oregon Trail. A former slave Hiram Young owned the largest business in Independence: he made wagons and ox yokes.

The Oregon Trail followed the south side of the Platte River, whereas, the Mormon Trail followed the north side. The two trails joined on the North Platte River.

The Oregon Trail followed the south side of the Platte River, whereas, the Mormon Trail followed the north side. The two trails joined on the North Platte River.

Chimney Rock was considered by many as the end of the prairie and the start of the mountainous part of the Oregon and Mormon trails.

Chimney Rock was considered by many as the end of the prairie and the start of the mountainous part of the Oregon and Mormon trails.

The prairie was the grasslands from central Canada to Mexico and from West of the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains. According to Chittenden, plains and prairie are basically interchangeable terms. Plains was used more as a descriptive term for travel. Example, pioneers went across the plains to reach Oregon.

The prairie was the grasslands from central Canada to Mexico and from West of the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains. According to Chittenden, plains and prairie are basically interchangeable terms. Plains was used more as a descriptive term for travel. Example, pioneers went across the plains to reach Oregon.

Beyond Chimney Rock, the next Oregon-Mormon Trail landmark was Scott’s Bluff. The bluff was named for Hiram Scott whose body was found near the bluff in 1830.

Beyond Chimney Rock, the next Oregon-Mormon Trail landmark was Scott’s Bluff. The bluff was named for Hiram Scott whose body was found near the bluff in 1830.

Fort William (Fort Laramie – 1834) and Fort Bridger (1843) had a lasting effect on travel over the Oregon-California and Mormon trails. Built by mountain men William Sublette and Jim Bridger, these two trading post were the major supply and layover points on the Mormon, California, and Oregon trails for hundreds of thousands of weary travelers.

Fort William (Fort Laramie – 1834) and Fort Bridger (1843) had a lasting effect on travel over the Oregon-California and Mormon trails. Built by mountain men William Sublette and Jim Bridger, these two trading post were the major supply and layover points on the Mormon, California, and Oregon trails for hundreds of thousands of weary travelers.

A major confrontation with Native Americans occurred near Ft. Laramie in 1854. The arrogance and stupidity of Lt. John Grattan has remained in history as the “Grattan Massacre”. It began when a lame cow wandered into a nearby Sioux village, which the Indians promptly ate. Lieutenant Grattan with twenty-eight soldiers left Fort Laramie to punish the Sioux. The Sioux offered a horse for the lame cow. Grattan didn’t even bother to refuse the offer. He ordered his men to fire, killing the village chief. Grattan and his men were promptly “massacred” by several hundred Sioux warriors.

A major confrontation with Native Americans occurred near Ft. Laramie in 1854. The arrogance and stupidity of Lt. John Grattan has remained in history as the “Grattan Massacre”. It began when a lame cow wandered into a nearby Sioux village, which the Indians promptly ate. Lieutenant Grattan with twenty-eight soldiers left Fort Laramie to punish the Sioux. The Sioux offered a horse for the lame cow. Grattan didn’t even bother to refuse the offer. He ordered his men to fire, killing the village chief. Grattan and his men were promptly “massacred” by several hundred Sioux warriors.

On a single day in June 1850, more than 2,000 people and 550 wagons passed by Fort Laramie.

On a single day in June 1850, more than 2,000 people and 550 wagons passed by Fort Laramie.

The abundance of grass and good water next to Independence Rock made it a welcome stopping point for every wagon train. The goal was to arrive at Independence Rock by the 4th of July in order to beat the winter snows in the Blue Mountains of Oregon.

The abundance of grass and good water next to Independence Rock made it a welcome stopping point for every wagon train. The goal was to arrive at Independence Rock by the 4th of July in order to beat the winter snows in the Blue Mountains of Oregon.

Some emigrants, including my great-great grandfather in 1847, carved their names, dates, or initials on Independence Rock. In 1860, Sir Richard Burton calculated there were between forty and fifty thousand names written on Independence Rock.

Some emigrants, including my great-great grandfather in 1847, carved their names, dates, or initials on Independence Rock. In 1860, Sir Richard Burton calculated there were between forty and fifty thousand names written on Independence Rock.

Independence Rock covers twenty-seven acres next to the Sweetwater River. Seven hundred feet wide, nineteen hundred feet long, and one hundred and thirty six feet high, the solitary rock is over a mile in circumference.

Independence Rock covers twenty-seven acres next to the Sweetwater River. Seven hundred feet wide, nineteen hundred feet long, and one hundred and thirty six feet high, the solitary rock is over a mile in circumference.

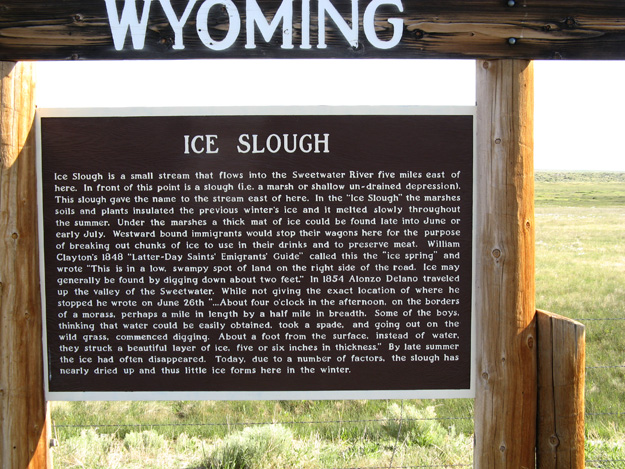

Ice Slough was a shallow basin just before South Pass. Ice from the previous winter was insulated under a two- to three-foot turf and could be dug out during the hot summer months.

Ice Slough was a shallow basin just before South Pass. Ice from the previous winter was insulated under a two- to three-foot turf and could be dug out during the hot summer months.

South Pass marked the halfway point on the Oregon Trail. Expecting a narrow alpine pass, emigrants were surprised by the gradual approach leading to a broad, relatively flat plain some twenty miles wide.

South Pass marked the halfway point on the Oregon Trail. Expecting a narrow alpine pass, emigrants were surprised by the gradual approach leading to a broad, relatively flat plain some twenty miles wide.

South Pass and Bend of the Bear River near Soda Springs, Idaho provided open passes through the Rocky Mountains. These passes allowed a wagon train to go from Independence, Missouri to the foothills of the Blue and Sierra mountains without going through a forest of pine trees.

South Pass and Bend of the Bear River near Soda Springs, Idaho provided open passes through the Rocky Mountains. These passes allowed a wagon train to go from Independence, Missouri to the foothills of the Blue and Sierra mountains without going through a forest of pine trees.

Pacific Spring was the first dependable water on the Pacific side of the Continental Divide.

Pacific Spring was the first dependable water on the Pacific side of the Continental Divide.

The next major stop on the Mormon-Oregon Trail was Fort Bridger.

The next major stop on the Mormon-Oregon Trail was Fort Bridger.

Replica of Fort Bridger, Lyman, Wyoming

Replica of Fort Bridger, Lyman, Wyoming

There were two major cutoffs on the Oregon trail that bypassed Fort Bridger. The Sublette Cutoff and the Lander Trail.

There were two major cutoffs on the Oregon trail that bypassed Fort Bridger. The Sublette Cutoff and the Lander Trail.

The waterless semi-arid land crossed by Sublette’s Cutoff was arguably one of the worst stretch on the Oregon Trail. In July 1844, the California bound Stevens-Townsend-Murphy wagon train, guided by Isaac Hitchcock and Caleb Greenwood, left the Oregon-California Trail nine and a half miles southwest of the “Parting of the Ways” marker on Highway 28. About 15 miles west of South Pass the Greenwood Cut-off…due to an error in the 1849 Joseph E. Ware guide book, the Greenwood Cut-Off name was changed to the Sublette Cut-off…it is interesting to note the Sublette Cut-off was named for Solomon Sublette, not his brother William Sublette. The Sublette-Greenwood Cut-off joined the Oregon-California trail in the Bear River Valley near Cokeville, Wyoming.

The waterless semi-arid land crossed by Sublette’s Cutoff was arguably one of the worst stretch on the Oregon Trail. In July 1844, the California bound Stevens-Townsend-Murphy wagon train, guided by Isaac Hitchcock and Caleb Greenwood, left the Oregon-California Trail nine and a half miles southwest of the “Parting of the Ways” marker on Highway 28. About 15 miles west of South Pass the Greenwood Cut-off…due to an error in the 1849 Joseph E. Ware guide book, the Greenwood Cut-Off name was changed to the Sublette Cut-off…it is interesting to note the Sublette Cut-off was named for Solomon Sublette, not his brother William Sublette. The Sublette-Greenwood Cut-off joined the Oregon-California trail in the Bear River Valley near Cokeville, Wyoming.

The Sublette Cut-off was about 70 miles shorter than the Fort Bridger route. After crossing the Big Sandy, there was 45 to 50 miles of desert before reaching the Green River…45 miles would be roughly four days without water. Some wagon trains passed through this dry stretch by traveling non-stop to the Green River. After crossing Green River, the Sublette Cut-off crossed a semi-aired mountain range to connect with the Oregon-California Trail near Cokeville, Wyoming.

The Sublette Cut-off was about 70 miles shorter than the Fort Bridger route. After crossing the Big Sandy, there was 45 to 50 miles of desert before reaching the Green River…45 miles would be roughly four days without water. Some wagon trains passed through this dry stretch by traveling non-stop to the Green River. After crossing Green River, the Sublette Cut-off crossed a semi-aired mountain range to connect with the Oregon-California Trail near Cokeville, Wyoming.

The other Oregon Trail cutoff was the Lander Trail. The trail left the Oregon Trail about eight miles east of South Pass and rejoined at the bend of the Bear River.

The other Oregon Trail cutoff was the Lander Trail. The trail left the Oregon Trail about eight miles east of South Pass and rejoined at the bend of the Bear River.

This area was referred to as the ninth crossing of the Sweetwater. A Pony Express station, a trading post and an army fort was in the area. The area is now the Burnt Ranch.

On the Bend of the Bear River, Steamboat Springs was a three-foot geyser emitting a high-pitched whistle similar to steamboats on the Missouri River. Steamboat Springs was the principal feature of a group of mineral springs collectively known as the Soda Springs. Located on the outskirts of Soda Springs, Idaho, some of these springs are now covered by the Alexander Reservoir.A minister proclaimed, “Hell is not more than a mile from this place.”

On the Bend of the Bear River, Steamboat Springs was a three-foot geyser emitting a high-pitched whistle similar to steamboats on the Missouri River. Steamboat Springs was the principal feature of a group of mineral springs collectively known as the Soda Springs. Located on the outskirts of Soda Springs, Idaho, some of these springs are now covered by the Alexander Reservoir.A minister proclaimed, “Hell is not more than a mile from this place.”

Fort Hall built in 1834 by Nathaniel Wyeth was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company (1837-1856) during a major part of the Oregon-California migration.

Fort Hall built in 1834 by Nathaniel Wyeth was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company (1837-1856) during a major part of the Oregon-California migration.

Since Hudson’s Bay Company wanted to keep American trappers and immigrants out of the Oregon Territory, the use of Fort Hall as a supply point for Oregon Trail pioneers has been widely over emphasized.

Since Hudson’s Bay Company wanted to keep American trappers and immigrants out of the Oregon Territory, the use of Fort Hall as a supply point for Oregon Trail pioneers has been widely over emphasized.

Roughly thirty miles north of the Oregon Trail, it is difficult to understand pioneers traveling five day out of the way for a rest stop or to repair wagons.

Roughly thirty miles north of the Oregon Trail, it is difficult to understand pioneers traveling five day out of the way for a rest stop or to repair wagons.

Hugh Grant refused supplies to the 1843 Chiles wagon train led by Joseph Walker, until Walker told Grant the wagon train was going to California, not Oregon.

Hugh Grant refused supplies to the 1843 Chiles wagon train led by Joseph Walker, until Walker told Grant the wagon train was going to California, not Oregon.

Walker sent Joseph Chiles and a few men to the Hudson’s Bay Fort Boise, but they were refused supplies there as well. The Fort Boise traders did give them a crude map to get over the Sierra Mountains to Sutter’s Mill.

Walker sent Joseph Chiles and a few men to the Hudson’s Bay Fort Boise, but they were refused supplies there as well. The Fort Boise traders did give them a crude map to get over the Sierra Mountains to Sutter’s Mill.

After Oregon became a United States Territory in 1846, the Hudson’s Bay trader Hugh Grant continued to buy furs from Americans, primarily Peg-leg, Smith, and offered supplies to the emigrants. Grant left Fort Hall in 1848.

After Oregon became a United States Territory in 1846, the Hudson’s Bay trader Hugh Grant continued to buy furs from Americans, primarily Peg-leg, Smith, and offered supplies to the emigrants. Grant left Fort Hall in 1848.

In 1849, General Persifor F. Smith wrote from Vancouver to authorities in Washington about abandoning Fort Hall. General Smith wrote…If a post were established at Ft. Hall to assist emigrants, it would be nearly useless, because they follow a new route more to the southward…the Hudspeth Cutoff.

In 1849, General Persifor F. Smith wrote from Vancouver to authorities in Washington about abandoning Fort Hall. General Smith wrote…If a post were established at Ft. Hall to assist emigrants, it would be nearly useless, because they follow a new route more to the southward…the Hudspeth Cutoff.

Hudson’s Bay Company abandoned Fort Hall in 1856.

Hudson’s Bay Company abandoned Fort Hall in 1856.

The Blue Mountains in Oregon were about half as high in elevation as South Pass, but they were the hardest mountain range to cross on the Oregon Trail.

The Blue Mountains in Oregon were about half as high in elevation as South Pass, but they were the hardest mountain range to cross on the Oregon Trail.

A series of waterfalls on the Columbia River at the Dalles forced pioneers to decide whether to build a raft and float down the Columbia River, or after 1846, use the safer Barlow Toll Road around Mt. Hood.

A series of waterfalls on the Columbia River at the Dalles forced pioneers to decide whether to build a raft and float down the Columbia River, or after 1846, use the safer Barlow Toll Road around Mt. Hood.

The end of the Oregon Trail was at Oregon City, not quite two thousand miles from Independence, Missouri.

The end of the Oregon Trail was at Oregon City, not quite two thousand miles from Independence, Missouri.

This is an ongoing article. As I come across items of interest, they will be added. If you send a comment, please put your name and email address in the form box. Your name will be used, unless you request otherwise, with your comments, but not your email address.

The Oregon Trail article was written by Ned Eddins of Afton, Wyoming.

Permission is given for material from this site to be used for school research papers.

Citation: Eddins, Ned. (article name) Thefurtrapper.com. Afton, Wyoming. 2002.

This site is maintained through the sale of my two historical novels. There are no banner adds, no pop up adds, or other advertising, except my books — To keep the site this way, your support is appreciated.

Mountains of Stone Winds of Change

There have been many requests for copies of pictures from the website. The best website pictures, and others from Jackson Hole, Yellowstone, and Star Valley, Wyoming, have been put on a CD. The pictures make beautiful screensavers, or can be used as a slide show in Windows XP. When ordering Mountains of Stone, request the CD and I will send it free with the book. The Winds of Change CD contains different pictures than those on the Mountains of Stone CD. To view a representative sample of the pictures on the CDs, click on…

To email a comment, a question, or a suggestion click on Mountain Man.

To return to the Emigrant Trails home page click on the Wagon Train logo.

Mormon Trail Astorians Fur Trade History

Oregon Country Fur Trappers Fur Trade Trivia

David Thompson Lewis and Clark Joseph Walker

Jedediah Smith Lander Cutoff South Pass

The trivia information comes from a wide variety of sources. The main sources are listed below. If I have missed a site, please let me know and I will add it.

References:

Ball John. Across the Plains to Oregon, 1832. Online Edition. Mtmen.org.

Ghent, W. J. The Early Far West. Longmans, Green and Co. New York, N.Y. 1931.

Gilbert, Bil. Westering Man The Life of Joseph Walker. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman, Oklahoma. 1985.

Gowans, Fred. Rocky Mountain Rendezvous. Perrigrine Smith Books Layton, Utah. 1985.

Gray, William H. A History of Oregon 1792 – 1849. Harris & Holman; New York, New York. 1870.

Leonard, Zenas. Adventures of a Mountain Man. Bison Books. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, Nebraska. 1978.

Merrill Mattes, The Great Platte River Road.

John Unruh, Jr. The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-60

Internet Sources:

http://www.americanwest.com/trails/pages/oretrail.htm.

http://www.canadiana.org/hbc/hist/hist10_e.html

http://www.over-land.com/trore.html#general

http://www.nps.gov/whmi/educate/ortrtg/ortrtg4.htm

http://www.nativeamericans.com/